Hallucinogenic plants have been part of the human experience for thousands of years, with users aware of their potential for healing, transformation, and growth – as well as their dangers – since as far back as prehistory. Now that public attention has been captured by these extraordinary plants, it is more important than ever to understand the history, pharmacology, and therapeutic potential of psilocybin and other psychedelics.

History

There are more than 100 species of psilocybin mushrooms worldwide, with samples found everywhere from Latin and North America to Europe and Asia. Given this geographic distribution, it is unsurprising that various cultures throughout history have incorporated their use into ceremonial and religious practices.

For instance, the Aztecs reportedly served a Psilocybe species known as teōnanācatl – the “divine mushroom” – at the coronation of Emperor Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin. In Spain, artwork depicting Psilocybe hispanica has led researchers to hypothesize that the ritual use of magic mushrooms may have begun in Europe as early as 4000BC. Some, like Terrence McKenna, have gone as far as to propound the Stoned Ape Hypothesis, which asserts that our long-term use of psilocybin mushrooms in prehistoric times led to epigenetic changes that were responsible for rapid increases in intelligence. While most academics are sceptical of such claims, there is little doubt that psilocybin mushrooms have an extensive history of influencing human behaviour.

After becoming an essential part of the US countercultural movement in the 1960s, public opinion on psilocybin and other psychedelics began to shift by the middle of the decade – in no small part due to a PR campaign by the US Government – culminating in their prohibition. The golden age of psychedelic research (1950-1965), wherein more than a thousand scientific papers were published, had come to an end.

Upon psilocybin’s reclassification as a Schedule I substance in 1970, research largely ground to a halt until after the turn of th

e century, when researchers at the University of Arizona discovered that psilocybin was associated with acute reductions in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms. Since then, research has picked up pace, with UCLA, Johns Hopkins University, New York University, and Imperial College leading the way. Moreover, in 2018, COMPASS Pathways secured Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA for use of psilocybin in treatment-resistant depression.

How does psilocybin work – and is it safe?

Upon ingestion, psilocybin is rapidly converted to psilocin by the liver. Psilocin then acts as a partial agonist for some types of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors (serotonin receptors), which leads to the profound mood and perceptual changes reported by users. The psychomimetic effects of psilocin can be aborted with 5-HT2A antagonists (e.g. ketanserin, trazodone).

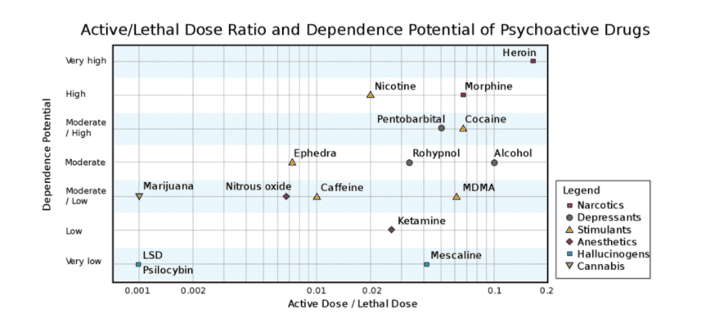

Additionally, psilocin indirectly raises the concentration of dopamine – a neurotransmitter linked to arousal and reward – in the basal ganglia, and since dopamine antagonists like haloperidol seem to block some subjective effects of psilocin, it is assumed that there is a dopaminergic component to the experience. Overall, psilocybin is approximately 100 times less potent than lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), and its effects persist about half as long.

Psilocybin is generally well tolerated by healthy individuals, with hormone levels, liver function, and blood sugar typically remaining constant throughout an experience (one study found these levels to be constant for up to 21 days of consecutive use at increasing doses). However, there is evidence that those with a predisposition towards psychotic disorders are at risk of developing overt symptoms or dangerous behavior – though psychotic disorders are not caused by psychedelics. Additionally, those with cardiovascular issues like untreated hypertension should abstain from psilocybin therapy due to its effects on heart rate and blood pressure. Finally, “bad trips” are relatively rare, and seem to arise at high doses and in uncontrolled environments for those who are already vulnerable.

Therapeutic Potential of Psilocybin

Since the 1960s, clinical trials have suggested that psilocybin might be efficacious in treating a bevy of conditions, but conclusive data on therapeutic applications are still being gathered. Non-exhaustively, psilocybin is purported to be helpful in treating:

-

- Depressive disorders (including treatment-resistant depression)

- Anxiety disorders

- Substance abuse disorders

- Anorexia

- Obesity

- Cluster headaches

- Personality disorders

In 2011, Roland Griffiths and colleagues published a study suggesting that – in addition to promoting increases in aesthetic appreciation, creativity, and imagination in users – a single high-dose of psilocybin may result in durable personality changes, with approximately half of healthy participants recording increases in openness (as measured by the NEO Personality Inventory). A follow up study published in 2017 found that doses of 20-30mg total elicited mystical type experiences that brought about lasting changes in altruism, gratitude, and connection to others when combined with spiritual practices like regular meditation.

In 2016, researchers at Imperial College London found that psilocybin coupled with psychological support seemed to “markedly reduce” depressive symptoms in twelve patients with unipolar treatment-resistant depression. Participants reported improvements in anxiety symptoms as well as their ability to take pleasure in their lives. Similar effectiveness was found in a randomized double-blind study examining the effects of psilocybin on depressive symptoms in patients with life-threatening cancer.

Notably, while the effects of psilocybin last anywhere between two and six hours, antidepressant effects appear to persist long-term (six months), with those who underwent the experience commonly reporting it as among the most meaningful in their lives.

The reasons for this effectiveness are still being investigated but may have to do with altered default mode network (DMN) activity. Neuroscientist David Nutt, who conducted an earlier study on the neural correlates of psychedelic states, found that psilocybin seemed to downregulate chatter between areas of the brain associated with sense of self. In an interview with Psychology Today, Dr. Nutt commented that the brains of people who get into depressive thinking are overconnected in this area – leading to overwhelming self-negativity – and that loosening them could be the key to providing relief.

Regardless of the exact mechanism, interest in psilocybin and other psychedelics has now exploded, with researchers exploring effectiveness for a range of indications including, e.g., anorexia nervosa, nicotine and alcohol addiction, and even obesity. For instance, at the recently founded Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelics and Consciousness Research, investigators have launched a clinical trial to determine whether two moderate to high doses of psilocybin can alleviate symptoms of anorexia nervosa when combined with motivational interview-based therapy. Moreover, studies examining the potential of psilocybin for smoking cessation and alcohol use disorder have revealed encouraging data, with additional studies currently recruiting participants.

What’s next?

Despite positive early signals, more data from large scale studies is required. Until organizations like COMPASS Pathways and others conclude Phase II and III clinical trials and secure regulatory approval, patient access will remain limited and confined to underground treatments or psychedelic retreats (both of which carry significant risks).

Despite the challenges that remain, there are clearly ample reasons to be optimistic. With the increased attention on psilocybin and other psychedelics, as well as a growing awareness that current interventions are not working, momentum has shifted in favor of these revolutionary substances. The trick will be to resist the urge to declare psilocybin a panacea, and ensure that we continue to prioritize patient safety, high-quality data collection, and engaging everyone in the healthcare continuum.

Founders’ Thoughts

“This isn’t a place to be fast and loose,” said George Goldsmith, Co-Founder of COMPASS Pathways, in a recent interview with The Telegraph.

“It’s a place to do the highest quality science at the biggest and best scale you can. But we need to get it absolutely right. Psychedelic research was out in the cold for 50 years. If we get it wrong, are we going to wait for another 50?”